In this blog post, I will be writing about my experiences learning Functional Reactive Programming (FRP). I will try to explain the basics of Cycle.js and FRP and what I have learned while building Meeting Price Calculator in Cycle.js. When I started learning Cycle.js, I did not know what Reactive Programming was and I had almost no experience in Functional Programming.

Background

I first heard about Cycle.js in 2015 when I started as a summer employee at Futurice . Andre Staltz , the creator of Cycle.js, used to work at Futurice and was demoing it in a WWWeeklies presentation. I got interested in it and tried it out for a bit. Later that summer I was also part of an internal project where we started using Cycle.js. However, it was not until March 2017 that I really started building something with Cycle.js.

Meeting Price Calculator

In March 2017, I seriously wanted to learn Cycle.js. I started literally by “building something” as you can see from the first commit message in the below screenshot.

The current functionality and look of the application is best described by visiting the site or by the gif below.

The idea for the application came from my personal frustration in long meetings at work. Sometimes meetings are useful and worth the cost, but most of the meetings are too long and ineffective or just useless. The idea is to have this calculator on a big screen during a meeting to make everyone more effective and aware of the real cost of multiple persons sitting in a room and discussing. I haven’t actually dared to do that during a real meeting yet.

Cycle.js Basics

You might not have heard about Cycle.js, since it is not as popular as React or Vue or others. However, it’s a proper and mature JS Framework used in production by several projects.

"Oh yeah, yet another JS Framework" – you might think.

That’s not the case with Cycle.js. It’s different. It’s not like any other framework out there.

Please note that I’m no expert in Cycle.js or FRP, but I’ll try to explain things as I understand them and how I learned them. If you have any feedback on the content of this blog post, I’ll gladly hear about that.

Let’s see what the official documentation describes it like:

“A functional and reactive JavaScript framework for predictable code”

– Source: cycle.js.org

In order to understand what that means, we have to understand the following three concepts:

- Functional Programming

- Reactive Programming

- Predictable code

I will do my best in trying to explain what these mean in a simple and understandable way.

Functional Programming

Functional Programming (FP) is a popular programming paradigm where the main idea is to avoid using global state, mutable data or side effects.

In FP, data flows through pure functions, meaning that the function has no side effects.

Side effects in this context means changing something outside the function scope, like changing a global variable or sending a HTTP request.

A pure function should only have inputs and return some outputs, without mutations.

A super simple example of a function that does not follow the functional paradigm:

let counter = 0;

const incrementCounter = () => (counter += 1);

The same function as a pure function that has no side effects:

const incrementCounter = (counter) => counter + 1;

If the ES6 arrow function syntax is unfamiliar to you, the first example means a function that takes no parameters and after the arrow (=>) is the function body.

In the second example, the function takes one parameter and returns that parameter incremented by one.

Curly braces or return statement are not needed for single-line function bodies.

The main difference here is that the first example mutates a global variable as opposed to the second example, which takes a variable called counter and returns a new variable that is the counter incremented by one.

FP is of course a lot more than this and I’m no hard-core-FP-enthusiast, but for now understanding the basic ideology is enough. Learning FP will help you write code that is easy to test and maintain. Testing a pure function is easy, since you don’t need to care about the world outside of the function you are testing. Just pass the inputs and check if the outputs are as expected. We will see how this gives us some nice properties when testing Cycle.js applications later in this post.

Reactive Programming

Reactive Programming (RP) is a programming paradigm based on asynchronous events streams, meaning sequences of events happening over time. If the concept of streams is unfamiliar to you, you can think of streams as an array that will receive values over time. An example stream could be a click stream, which receives events when the user clicks something on a page. In your code you can then define how to react to those events happening over time. Streams have a start and they may also have an end. Cycle.js supports using different stream libraries, but there is one that is designed for the exact purpose of Cycle.js. It’s called xstream . I’m using xstream in my application.

“In short, a Stream in xstream is an event stream which can emit zero or more events, and may or may not finish. If it finishes, then it does so by either emitting an error or a special “complete” event.”

– Source: Cycle.js documentation about RP

A good example of reactivity is using formulas in Excel spreadsheets. The visible values are immediately reacting to the changes in the data. You don’t have to call any update functions to update the calculations, but the cells react to changes in the data.

In RP, modules are responsible for reacting to changes and not responsible for changing other modules like in traditional, so-called passive programming.

This is visualized in the image below where Bar is reacting to an event happening in Foo instead of Foo poking Bar for a change.

This is why In RP, understanding how a module works is a lot easier than in passive programming. You only need to look at the code for that module, and not all over the codebase. All of its future is defined there. No remote modules will change it. The only changes happening are declared in the module and these changes can be based on events emitted by other modules.

The opposite of RP, passive programming, is when the change to a module is defined somewhere else.

This causes the module to have public methods, like say updateTotalCount or similar that are then called by other modules when something happens.

I have been there, struggling with looking for who’s responsible for sending emails after a successful payment in an E-commerce plaftorm. In the end I found out that the payment module was handling the email sending after receiving a successful payment. What would have happened if the payment module was replaced with something else? Who would have thought that the payment module was actually responsible for sending the emails as well?

“Whenever the module being changed is responsible for defining that change.”

– Andre Staltz about the definition of Reactive Programming

There is a lot more to RP than what I am able explain in a blog post. Take a look at Cycle.js documentation about RP , if you want to learn more. On a side-note, the documentations for Cycle.js are well formulated and kept up-to-date.

Functional Reactive Programming

Functional Reactive Programming (FRP) simply combines both functional and reactive paradigms, picking the best of both worlds. Cycle.js is a nice example of combining these two.

Predictable Code

In order to say that Cycle.js code is predictable we need to understand what predictable and unpredictable code means.

Having your codebase full of global variables and impure functions easily results in unpredictable code. You can never be sure what the output of a function is if it depends on some global state or global variable or has some side effects.

In other words, writing predictable code means writing code that you can reason about. Functions that are pure will always have the same output with a given input, no matter how many times they are called or how the stars are aligned at the exact time of execution. This is the case with Cycle.js. You can see the interaction and data flow by reading the code, without having to think about global state or event listeners defined somewhere else. In reactive code, you can see the interactions happening in the module’s code because the module is in control of how to react to different events and not the other way round like in passive programming.

Predictability comes from moving side effects away from your modules and only having pure functions. This way you can predict what the result will be when you call a function in your code. Global variables or global state do not affect the result of a function, only the inputs affect the output of a function.

Of course, in the end it’s up to you how organized and predictable code you write.

One of the best things about Cycle.js code is that it’s basically just TypeScript (or JS), but on the other hand, that’s also the worst part of it as you might know if you have used JS/TS for a while. There is no strict language level enforcement for good practices or protection against runtime crashes.

However, writing my code using TypeScript instead of plain JavaScript has helped me a lot in figuring out how to work with Streams.

Cycle.js And Why It Is Different

So, now that we have the required background knowledge, let’s focus on explaining what Cycle.js is and how it differs from the other frameworks out there.

Separation of Concerns

In Cycle.js, the side effects and the application logic are separated.

The logic part is purely functional and reactive code without side effects.

This logic part can be thought of as a main() function in your Cycle.js code.

The function is pure, it only receives sources as inputs and returns sinks as outputs.

It does not do any side effects.

Sources are the inputs to a Cycle app.

They can be reads from the DOM, or HTTP responses for example.

The sinks returned by the main function can be the writes happening to the DOM, or the HTTP request to be sent.

The outputs of a cycle app are a function on its inputs. The inputs also depend on the outputs of the function.

Thus the name Cycle.

Side effects happen in the so-called drivers.

In the example below, we can see the DOM Driver which handles writing to the DOM and reading from the DOM.

Reads from DOM can be user intents like click events or input events.

Source: Cycle.js documentation

Component Model

In Cycle.js, an application is just a function.

This means that you can easily nest functions inside a function.

That’s how easy it is to create nested components in Cycle.js.

In addition to this, Cycle.js provides a way to isolate the components from each other.

This way you can easily create reusable components without thinking about conflicting namespaces and selectors.

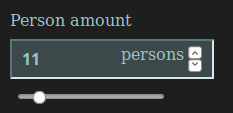

In my application I used this technique in order to create a reusable component called sliderInput .

It is used twice in my application with slightly different input parameter streams or so-called props in the React-world.

Source: Cycle.js documentation

Model-View-Intent

Model-View-Controller pattern does not really work nicely for reactive programming due to it’s nature.

In MVC, the controller is imperatively controlling other components.

What would the controller even be needed for in RP?

That’s why in Cycle.js we keep the MVC idea while avoiding a proactive Controller .

Instead of the Controller, we have something that’s called Intent.

The pattern that emerges is thus Model-View-Intent (MVI), with the following constituents:

Model

- Input: user interaction events from the Intent.

- Output: data events.

View

- Input: data events from the Model.

- Output: a Virtual DOM rendering of the model, and raw user input events (such as clicks, keyboard typing, accelerometer events, etc).

Intent

- Input: raw user input events from the View.

- Output: model-friendly user intention events.

MVI is a pattern that works well with Cycle.js. In fact, this is actually what the main idea of Cycle.js is based on .

Code Examples

Now you might be wondering what Cycle.js code looks like. I’ll use the previously mentioned sliderInput component as an example.

I have split the component code into 5 different files, following the MVI-pattern:

- index.ts

- model.ts

- view.ts

- intent.ts

- styles.ts

Where styles.ts is not very important at this point.

It simply contains the styles for the component.

Let’s see what the code looks like, starting from the view.ts which is a function that receives a State stream and returns a stream of VNodes, that will then get rendered in the DOM.

view.ts:

import xs from 'xstream';

import { VNode, div, input, span, label } from '@cycle/dom';

import { State } from './index';

import { styles } from './styles';

export default function view(state$: xs<State>): xs<VNode> {

return state$.map(({ description, unit, min, max, step, value }) =>

div(`.${styles.sliderInput}`, [

label(description),

input(`.SliderInput-input .${styles.numberInput}`, {

attrs: {

type: 'number',

min,

max,

step,

},

props: { value },

}),

span(`.${styles.sliderInputUnit}`, unit),

input('.SliderInput-input', {

attrs: {

type: 'range',

min,

max,

step,

},

props: { value },

}),

])

);

}

Below is a screenshot of how a SliderInput component might look in the current design.

The view function maps the state stream into a stream of VNodes.

It picks the interesting value from the state object and ouputs a div containing two inputs; one slider and one number input field.

So, where does the state stream come from and who’s calling the view function?

We can see in the index.ts the components “main” function, SliderInput, which looks like this that it is responsible for calling the view function:

export default function SliderInput(sources: Sources): Sinks {

const actions: SliderInputActions = intent(sources.DOM);

const reducer$: xs<Reducer> = model(actions);

const state$: xs<State> = (sources.onion.state$ as any) as xs<State>;

const vdom$: xs<VNode> = view(state$);

const sinks: Sinks = {

DOM: vdom$,

onion: reducer$,

};

return sinks;

}

This follows the basic MVI-pattern in Cycle.js using cycle-onionify for state management. More about that in the next chapter. The above example component code could be simplified into the following piece of code, if we did not use onionify and did not care about readability:

export default function SliderInput(sources: Sources): Sinks {

return {

DOM: view(model(intent(sources.DOM)));

}

}

This means that the view is a function of the model and the intent.

The output of of the function will also be the input of the function, thus the Cycle.

Let’s see how the model and intent look in order to understand what the state stream consists of.

Intent means basically the user’s intentions, user actions, HTTP responses or similar. In this case, Intent is responsible for mapping the user input stream into an actions object which contains action streams.

intent.ts:

import xs from 'xstream';

export interface SliderInputActions {

ValueChangeAction$: xs<number>;

}

export default function intent(domSource): SliderInputActions {

const ValueChangeAction$ = domSource

.select('.SliderInput-input')

.events('input')

.map((inputEv) => parseInt((inputEv.target as HTMLInputElement).value));

return {

ValueChangeAction$,

};

}

This function selects the elements that have the class SliderInput-input and maps all the input events into the value of the input field as an integer.

The returned object contains a stream that contains all the future values of the input field with that particular class.

Please note that due to using the same class for both the input fields, range and number field, the change event is emitted if either of the input fields receive an input event.

The model is then reacting to these value changes and updating the state accordingly.

model.ts:

import xs from 'xstream';

import { State, Reducer } from './index';

import { SliderInputActions } from './intent';

export default function model(actions: SliderInputActions): xs<Reducer> {

const defaultReducer$: xs<Reducer> = xs.of(

(prev?: State): State =>

prev !== undefined

? prev

: {

description: 'description',

unit: 'unit',

min: 1,

max: 100,

step: 1,

value: 100,

}

);

const valueChangeReducer$: xs<Reducer> = actions.ValueChangeAction$.map(

(value) => (prevState: State): State => ({

...prevState,

value,

})

);

return xs.merge(defaultReducer$, valueChangeReducer$);

}

We can see that the valueChangeReducer$ is responsible for updating the state when it receives a value change actions event.

The default reducer sets the default state for the component, so that it can render something if no values are passed to it.

State Management in Cycle.js

State management is well-known to be one of the biggest challenges in web development. There are tens of libraries which try to simplify state handling and help creating high quality web applications easily. Two of my favorite libraries (for React) are MobX and probably the most popular one, Redux .

However, In my experience, setting up Redux might feel quite confusing and the code verbose and full of boiler-plate.

In Cycle.js, the soon official state management solution is called cycle-onionify . I’m also using it in my application for state handling.

Note: In this blog post, I will not try to compare Redux, MobX and cycle-onionify. That might end up in another blog post at an undefined time. I will simply write about my experiences using cycle-onionify.

State in the above mentioned SliderInput component’s case looks like this:

export interface State {

description: string;

unit: string;

min: number;

max: number;

step: number;

value: number;

}

This cannot be the whole state of my application, right? No it’s not. It’s just the inner state of this isolated component. Using lenses, we can “zoom” in and out in the Application state, exposing as little as possible of the internal structure of a component to the outer components. In my case, the top-level application state looks like this:

export interface State {

startTime: moment.Moment;

duration: number;

currency: string;

personAmount: number;

avgPrice: number;

}

From that top-level state I pass down the relevant parts to the child components using lenses. The components then update the relevant parts of the top-level state when needed.

An example of this can be seen in a component called controls which receives the AppState and passes down parts of it to the SliderInput components and vice-versa.

export const lens = {

get: (state: AppState): State => ({

currency: state.currency,

personAmount: state.personAmount,

avgPrice: state.avgPrice,

}),

set: (state: AppState, childState: State) => ({

...state,

currency: childState.currency,

personAmount: childState.personAmount,

avgPrice: childState.avgPrice,

}),

};

In the above example, the personAmount and avgPrice parts of the childState are parts of the states of SliderInput components.

This can be seen in the lens below:

export const personAmountLens = {

get: (state: AppState): State => ({

description: 'Person amount',

unit: state.personAmount > 1 ? 'persons' : 'person',

min: 1,

max: 100,

step: 1,

value: state.personAmount,

}),

set: (state: AppState, childState: State) => ({

...state,

personAmount: childState.value,

}),

};

This means that even though the component needs a state that consists of multiple values, it only needs to expose the “final” result, the value, to the component above it.

Testing Cycle.js Applications

Testing Cycle.js applications is quite easy, since most of your functions are pure functions. Testing a pure function is easy since you know nothing outside of the function affects the output of the function and the function does not affect the outside world.

In testing Meeting Price Calculator specifically, it has been proven useful that in Cycle.js, time is just a dependency and you can inject or pass that to your functions. This makes testing a lot simpler. I am using jest for running tests and snapshot tests as well as html-looks-like in combination with jsverify and property-based testing for verifying that the views work correctly with any input values.

Recap

Key take aways:

- Cycle.js is a fully featured, mature framework for building web applications

- FRP can help you in writing predictable, easily testable code

- By keeping your functions pure, you make testing them easy

- MVI is a nice pattern, which gives you ways to split up files and responsibilities in code

Supporting Cycle.js

In addition to the community members, Cycle.js is maintained by the core team members. The project is funded by Open Collective contributions .

You can also support Cycle.js.

Learn More

If you are interested in learning more, check out these resources:

- PolyConf 16 / Dynamics of change: why reactivity matters/ Andre Staltz

- The introduction to Reactive Programming you’ve been missing

- Understand Reactive Programming using RxJS

- Using Cycle.js to view real-time satellite test data

- Awesome Cycle.js

- The Repository for Meeting Price Calculator

Acknowledgements

- Thanks to my employer Futurice for sponsoring open source development through Spice Program

- Thanks to Andre Staltz for reviewing my code and helping me simplify the state handling in my app

- Thanks to the awesome Cycle.js community members who are always willing to help when needed

- Thanks to Andre Staltz for reviewing this blog post and suggesting improvements to it

- Thanks to my colleague Fotis for proofreading this blog post and suggesting improvements to it